Monday Aug 12, 2013 | SARAH DiLORENZO for The Associated Press

[Study suggests Neanderthals were more advanced]

Study suggests Neanderthals were more advanced

Credit: The Associated Press

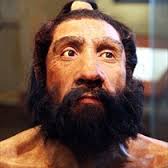

No brutes: New bone find suggests Neanderthals were more advanced than previously thought

PARIS (AP) — Researchers have found what they say are specialized bone tools made by Neanderthals in Europe thousands of years before modern humans are thought to have arrived to share such skills, a discovery that suggests modern man’s distant cousins were more advanced than previously believed.

In a paper published online Monday by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers discuss their discovery of four fragments of bone in southwestern France that they say were used as lissoirs, or smoothers, to make animal hides tougher and more water-resistant.

The researchers believe the oldest tool is 51,000 years old, while the other three are between 42,000 and 47,000 years old. Similar tools are still used by leather workers to this day.

Until now, scientists have believed that modern humans taught the Neanderthals how to make the tools, but modern humans are only believed to have reached central and western Europe 42,000 years ago.

The researchers say the discovery provides the first evidence that Neanderthals may have independently made specialized bone tools — that is, tools that could only be made from bone. Other early Neanderthal bone tools were simply replicas of their stone tools.

The find adds to an evolving understanding that these distant cousins weren’t perhaps the brutes they have come to represent in popular culture — but also confirms that there is still much we don’t know about them.

“It’s adding to a growing body of research, that’s growing quite rapidly at the moment, that’s showing that Neanderthals are capable and did produce tools … in a way that is much more similar to modern humans than we thought even a couple of years ago,” said Rachel Wood, an archaeologist and researcher in radiocarbon dating at the Australian National University who was not involved in the study.

Shannon P. McPherron, one of the archaeologists involved in the dig and an author of the article, said it’s possible that other Neanderthal dig sites contain similar tools. However, since they were probably used until the tips broke off — leaving a fragment just a few centimeters long, as was the case with three of the tools found — they would be difficult to spot.

“It’s like looking at pencil leads,” he said, expressing hope the find would fuel more discoveries. “Once you sort of get the pattern, it’s a lot easier to spot them.”

McPherron even held out the possibility that Neanderthals were the ones who showed modern humans how to make lissoirs, although modern humans clearly started making specialized bone tools on their own.

“It’s pretty rare that you hear that argument, so it’s nice to hear it,” said Wood, who noted that mostly researchers talk about modern humans influencing Neanderthals.

Even though the age of the tools suggested Neanderthals began making them on their own, McPherron, of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and his co-authors didn’t rule out the possibility that they did adopt this technology from modern humans. But that would mean modern humans entered Europe much earlier than thought.

Scientists have recently begun to ask new questions about whether and for how long Neanderthals and modern humans co-existed. While the two groups were long thought to have intermingled and even interbred for thousands of years in Europe, a study published earlier this year suggested that Neanderthals went extinct in their last European refuge much earlier than previously thought, as long as 50,000 years ago — thousands of years before modern humans were thought to have arrived.

“Our find could indicate that there was a long period of interaction, where modern humans came into Europe and sent ripples through the pond, and then maybe withdrew and then came back again,” McPherron said.

But Sabine Gaudzinski-Windheuser, a professor at Mainz University who also wasn’t involved with the study, said the evidence was a bit thin to draw any conclusions about the interaction between the two groups.

“Based on this find to make statements about the transition or the interaction between Neanderthals and modern humans is really, well, you really have to stretch the evidence very far to get to this conclusion,” she said.