By Gordon Corera

Security correspondent, BBC NewsPublished19 hours agoShare

Doctors, scientists, intelligence agents and government officials have all been trying to find out what causes “Havana syndrome” – a mysterious illness that has struck American diplomats and spies. Some call it an act of war, others wonder if it is some new and secret form of surveillance – and some people believe it could even be all in the mind. So who or what is responsible?

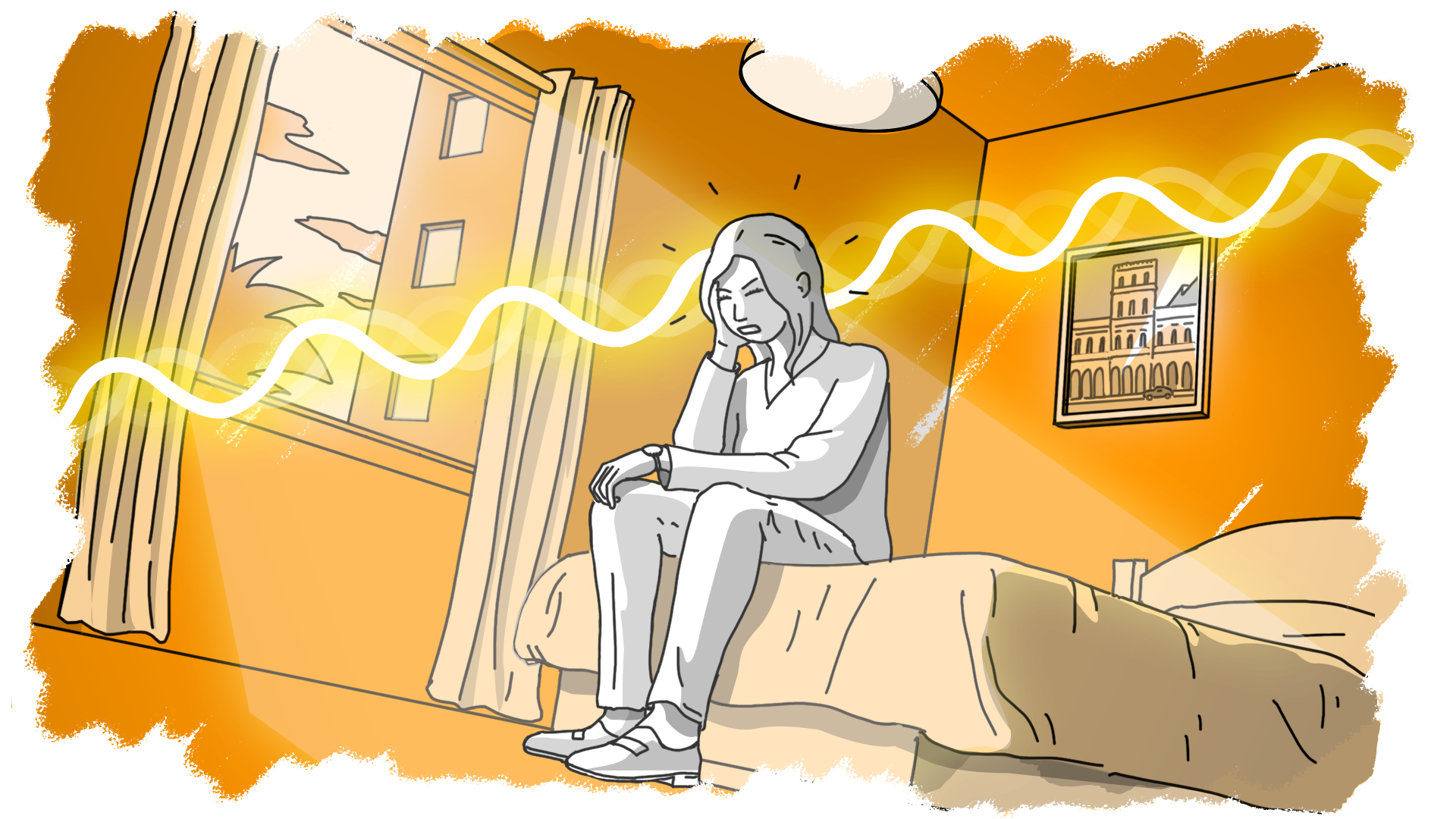

It often started with a sound, one that people struggled to describe. “Buzzing”, “grinding metal”, “piercing squeals”, was the best they could manage.

One woman described a low hum and intense pressure in her skull; another felt a pulse of pain. Those who did not hear a sound, felt heat or pressure. But for those who heard the sound, covering their ears made no difference. Some of the people who experienced the syndrome were left with dizziness and fatigue for months.

Havana syndrome first emerged in Cuba in 2016. The first cases were CIA officers, which meant they were kept secret. But, eventually, word got out and anxiety spread. Twenty-six personnel and family members would report a wide variety of symptoms. There were whispers that some colleagues thought sufferers were crazy and it was “all in the mind”.

Five years on, reports now number in the hundreds and, the BBC has been told, span every continent, leaving a real impact on the US’s ability to operate overseas.

Uncovering the truth has now become a top US national security priority – one that an official has described as the most difficult intelligence challenge they have ever faced.

Hard evidence has been elusive, making the syndrome a battleground for competing theories. Some see it as a psychological illness, others a secret weapon. But a growing trail of evidence has focused on microwaves as the most likely culprit.

In 2015, diplomatic relations between the US and Cuba were restored after decades of hostility. But within two years, Havana syndrome almost shut the embassy down, as staff were withdrawn because of concerns for their welfare.

Initially, there was speculation that the Cuban government – or a hard-line faction opposed to improving relations – might be responsible, having deployed some kind of sonic weapon. Cuba’s security services, after all, had been nervous about an influx of US personnel and kept a tight grip on the capital.

That theory would fade as cases spread around the world.

But recently, another possibility has come into the frame – one whose roots lay in the darker recesses of the Cold War, and a place where science, medicine, espionage and geopolitics collide.

When James Lin, a professor at the University of Illinois, read the first reports about the mysterious sounds in Havana, he immediately suspected that microwaves were responsible. His belief was based not just on theoretical research, but first-hand experience. Decades earlier, he had heard the sounds himself.

Since its emergence around World War Two, there had been reports of people being able to hear something when a nearby radar was switched on and began sending microwaves into the sky. This was even though there was no external noise. In 1961, a paper by Dr Allen Frey argued the sounds were caused by microwaves interacting with the nervous system, leading to the term the “Frey Effect”. But the exact causes – and implications – remained unclear.

Radio 4 – Crossing Continents

The Mystery of Havana Syndrome

In the 1970s, Prof Lin set to work conducting his experiments at the University of Washington. He sat on a wooden chair in a small room lined with absorbent materials, an antenna aimed at the back of his head. In his hand he held a light switch. Outside, a colleague sent pulses of microwaves through the antenna at random intervals. If Prof Lin heard a sound, he pressed the switch.

A single pulse sounded like a zip or a clicking finger. A series of pulses like a bird chirping. They were produced in his head rather than as sound waves coming from outside. Prof Lin believed the energy was absorbed by the soft brain tissue and converted to a pressure wave moving inside the head, which was interpreted by the brain as sound. This occurred when high-power microwaves were delivered as pulses rather than in the low-power continuous form you get from a modern microwave oven or other devices.

Prof Lin recalls that he was careful not to dial it up too high. “I did not want to have my brain damaged,” he told the BBC.

In 1978, he found he was not alone in his interest, and received an unusual invitation to discuss his latest paper from a group of scientists who had been carrying out their own experiments.

During the Cold War, science was the focus of intense super-power rivalry. Even areas like mind control were explored, amid fears of the other side getting an edge – and this included microwaves.

Prof Lin was shown the Soviet approach at a centre of scientific research in the town of Pushchino, near Moscow. “They had a very elaborate, very well-equipped laboratory,” Prof Lin recalls. But their experiment was cruder than his. The subject would sit in a drum of salty seawater with their head sticking out. Then microwaves would be fired at their brain. The scientists thought the microwaves interacted with the nervous system and wanted to question Prof Lin on his alternative view.

Curiosity cut both ways, and US spies kept close track on Soviet research. A 1976 report by the US Defense Intelligence Agency, unearthed by the BBC, says it could find no proof of Communist-bloc microwave weapons, but says it had learnt of experiments where microwaves were pulsed at the throat of frogs until their hearts stopped.

The report also reveals that the US was concerned Soviet microwaves could be used to impair brain function or induce sounds for psychological effect. “Their internal sound perception research has great potential for development into a system for disorienting or disrupting the behaviour patterns of military or diplomatic personnel.”

American interest was more than just defensive. James Lin would occasionally glimpse references to secret US work on weapons in the same field.

And while Prof Lin was in Pushchino, another group of Americans not far away were worried that they were being zapped by microwaves – and that their own government had covered it up.

For nearly a quarter of a century, the 10-storey US embassy in Moscow was bathed by a wide, invisible beam of low-level microwaves. It became known as ”the Moscow signal”. But for many years, most of those working inside knew nothing.

The beam came from an antenna on the balcony of a nearby Soviet apartment and hit the upper floors of the embassy where the ambassador’s office and more sensitive work was carried out. It had been first spotted in the 1950s and was later monitored from a room on the 10th floor. But its existence was a secret tightly held from all but a few working inside. “We were trying to figure out just what might be its purpose,” explains Jack Matlock, number two at the embassy in the mid-70s.

But a new ambassador, Walter Stoessel, arrived in 1974 and threatened to resign unless everyone was told. “That caused something like panic,” recalls Mr Matlock. Embassy staff whose children were in a basement nursery were especially worried. But the State Department played down any risk.

Then Ambassador Stoessel, himself, fell ill – with bleeding of the eyes as one of his symptoms. In a now declassified 1975 phone call to the Soviet ambassador to Washington, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger linked Stoessel’s illness to microwaves, admitting “we are trying to keep the thing quiet”. Stoessel died of leukaemia at the age of 66. “He decided to play the good soldier”, and not make a fuss, his daughter told the BBC.

From 1976 screens were installed to protect people. But many diplomats were angry, believing the State Department had first kept quiet, and then resisted acknowledging any possible health impact. This was a claim echoed decades later with Havana syndrome.

What was the Moscow signal for? “I’m pretty sure that the Soviets had intentions other than damaging us,” says Matlock. They were ahead of the US in surveillance technology and one theory was that they bounced microwaves off windows to pick up conversations, another that they were activating their own listening devices hidden inside the building or capturing information through microwaves hitting US electronic devices (known as “peek and poke”). The Soviets at one point told Matlock that the purpose was actually to jam American equipment on the embassy roof used to intercept Soviet communications in Moscow.

This is the world of surveillance and counter-surveillance, one so secret that even within embassies and governments only a few people know the full picture.

One theory is that Havana involved a much more targeted method to carry out some kind of surveillance with higher-power, directed microwaves. One former UK intelligence official told the BBC that microwaves could be used to “illuminate” electronic devices to extract signals or identify and track them. Others speculate that a device (even perhaps an American one) might have been poorly engineered or malfunctioned and caused a physical reaction in some people. However, US officials tell the BBC no device has been identified or recovered.

After a lull, cases began to spread beyond Cuba.

In December 2017, Marc Polymeropolous woke suddenly in a Moscow hotel room. A senior CIA officer, he was in town to meet Russian counterparts. “My ears were ringing, my head was spinning. I felt like I was going to vomit. I couldn’t stand up,” he told the BBC. “It was terrifying.” It was a year after the first Havana cases, but the CIA medical office told him his symptoms didn’t match the Cuban cases. A long battle for medical treatment began. The severe headaches never went away and in the summer of 2019 he was forced to retire.

Mr Polymreopolous originally thought he had been hit by some kind of technical surveillance tool that had been “turned up too much”. But when more cases emerged at the CIA which were all, he says, linked to people working on Russia, he came to believe he had been targeted with a weapon.

But then came China, including at the consulate in Guangzhou in early 2018.

Some of those affected in China contacted Beatrice Golomb, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, who has long researched the health effects of microwaves, as well as other unexplained illnesses. She told the BBC that she wrote to the State Department’s medical team in January 2018 with a detailed account of why she thought microwaves were responsible. “This makes for interesting reading,” was the non-committal response.

Prof Golomb says high levels of radiation were recorded by family members of personnel in Guangzhou using commercially available equipment. “The needle went off the top of the available readings.” But she says the State Department told its own employees that the measurements they had taken off their own back were classified.

A host of problems plagued early investigations. There was a failure to collect consistent data. The State Department and CIA failed to communicate with each other, and the scepticism of their internal medical teams caused tension.

Only one out of the nine cases from China was initially determined by the State Department to match the criteria for the syndrome based on Havana cases. That left others who experienced symptoms angry, and feeling as if they were being accused of making it up. They began a battle for equal treatment, which is still going on today.

As frustration grew, some of those affected turned to Mark Zaid, a lawyer who specialises in national security cases. He now acts for around two dozen government personnel, half from the intelligence community.

“This is not Havana syndrome. It’s a misnomer,” argues Mr Zaid, whose clients were affected in many locations. “What’s been going on has been known by the United States government probably, based on evidence that I have seen, since the late 1960s.”

Since 2013, Mr Zaid has represented one employee of the US National Security Agency who believed they were damaged in 1996 in a location which remains classified.

Mr Zaid questions why the US government has been so unwilling to acknowledge a longer history. One possibility, he says, is because it might open a Pandora’s Box of incidents that have been ignored over the years. Another is because the US, too, has developed and perhaps even deployed microwaves itself and wants to keep it secret.

The country’s interest in weaponising microwaves extended beyond the end of the Cold War. Reports say from the 1990s, the US Air Force had a project codenamed “Hello” to see if microwaves could create disturbing sounds in people’s heads, one called “Goodbye” to test their use for crowd control, and one codenamed “Goodnight” to see if they could be used to kill people. Reports from a decade ago suggested these had not proved successful.

But the study of the mind and what can be done to it has been receiving increased focus within the military and security world.

“The brain is being seen as the 21st Century battle-scape,” argues James Giordano, an adviser to the Pentagon and Professor in Neurology and Biochemistry at Georgetown University, who was asked to look at the initial Havana cases. “Brain sciences are global. It is not just the province of what used to be known as the West.” Ways to both augment and damage brain function are being worked on, he told the BBC. But it is a field with little transparency or rules.

He says China and Russia have been engaged in microwave research and raises the possibility that tools developed for industrial and commercial uses – for instance to test the impact of microwaves on materials – could have been repurposed. But he also wonders if disruption and spreading fear were also the aim.

This kind of technology may have been around for a while – and even have been used selectively. But that would still mean something changed in Cuba to get it noticed.

Bill Evanina was a senior intelligence official when the Havana cases emerged, and stepped down as the head of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center this year. He has little doubt about what happened in Havana. “Was it an offensive weapon? I believe it was,” he told the BBC.

He believes microwaves may have been deployed in recent military conflicts, but points to specific circumstances to explain a shift.

Cuba, 90 miles off the Florida coast, has long been an ideal site to collect “signals intelligence” by intercepting communications. During the Cold War, it was home to a major Soviet listening station. When Vladimir Putin visited in 2014, reports suggested it was being re-opened. China also opened two sites in recent years, according to one source, while the Russians sent in 30 additional intelligence officers.

But from 2015, the US was back in town. With its newly opened embassy and a beefed-up presence, the US was just beginning to establish its footing, collecting intelligence and pushing back against Russian and Chinese spies. “We were in a ground fight,” one person recalls.

Then the sounds began.

“Who had the most to benefit from the closing of the embassy in Havana?” asks Mr Evanina. “If the Russian government was increasing and promulgating their intelligence collection in Cuba, it was probably not good for them to have the US in Cuba.”

Russia has repeatedly dismissed accusations it is involved, or has “directed microwave weapons”. “Such provocative, baseless speculation and fanciful hypotheses can’t really be considered a serious matter for comment,” its foreign ministry has said.

And there have been sceptics about the very existence of Havana syndrome. They argue that the unique situation in Cuba supports their case.

‘Contagious’ stress

Robert W Baloh, a Professor of Neurology at UCLA, has long studied unexplained health symptoms. When he saw the Havana syndrome reports, he concluded they were a mass psychogenic condition. He compares this to the way people feel sick when they are told they have eaten tainted food even if there was nothing wrong with it – the reverse of the placebo effect. “When you see mass psychogenic illness, there’s usually some stressful underlying situation,” he says. “In the case of Cuba and the mass of the embassy employees – particularly the CIA agents who first were affected – they certainly were in a stressful situation.”

In his view, every-day symptoms like brain fog and dizziness are reframed – by sufferers, media and health professionals – as the syndrome. “The symptoms are as real as any other symptoms,” he says, arguing that individuals became hyper-aware and fearful as reports spread, especially within a closed community. This, he believes, then became contagious among other US officials serving abroad.

There remain many unexplained elements. Why did Canadian diplomats report symptoms in Havana? Were they collateral damage from targeting nearby Americans? And why have no UK officials reported symptoms? “The Russians have literally tried to kill people on British soil in recent years with radioactive materials, yet why are there no reported cases?” asks Mark Zaid. “I would probably put on pause the statement that no-one in the UK has experienced any symptoms,” responds Bill Evanina, who says the US is now sharing details with allies to spot cases.

Some instances may be unrelated. “We had a bunch of military folk in the Middle East who claimed to have this attack – turned out they had food poisoning,” says one former official. “We need to separate the wheat from the chaff,” reckons Mark Zaid, who says members of the public, some with mental health issues, approach him claiming to suffer from microwave attacks. One former official reckons around half the cases reported by US officials are possibly linked to attacks by an adversary. Others say the real number could be even smaller.

A December 2020 report by the US National Academies of Sciences was a pivotal moment. Experts took evidence from scientists and clinicians as well as eight victims. “It was quite dramatic,” recalls Professor David Relman of Stanford, who chaired the panel. “Some of these people literally were in hiding, for fear of further actions against them by whomever. There were actually precautions we had to take to ensure their safety.” The panel looked at psychological and other causes, but concluded that directed, high energy, pulsed microwaves were most likely responsible for some of the cases, similar to the view of James Lin, who gave evidence.

But even though the State Department sponsored the study, it still considers the conclusion only a plausible hypothesis and officials say they have not found further evidence to support it.

The Biden administration has signalled it is taking the issue seriously. CIA and State Department officials are given advice on how to respond to incidents (including ‘getting off the X’ – meaning physically moving from a spot if they feel they are getting hit). The State Department has set up a task force to support staff over what are now called “unexplained health incidents”. Previous attempts to categorise cases as to whether they met specific criteria have been abandoned. But without a definition, it becomes harder to count.

This year, a new wave of cases arrived – including Berlin and a larger group in Vienna. In August, a trip by US Vice-President Kamala Harris to Vietnam was delayed three hours because of a reported case at the embassy in Hanoi. Worried diplomats are now asking questions before taking foreign assignments with their families.

“This is a major distraction for us if we think that the Russians are doing things to our intelligence officers who are travelling,” says former CIA officer Polymreopolous, who finally received the medical treatment he wanted this year. “That’s going to put a crimp in our operational footprint.”

The CIA has taken over the hunt for a cause, with a veteran of the hunt for Osama bin Laden placed in charge.

Markers in the blood

An accusation that another state has been harming US officials is a consequential one. “That’s an act of war,” says Mr Polymeropolous. That makes it a high bar to reach. Policymakers will demand hard evidence, which so far, officials say, is still lacking.

Five years on, some US officials say little more is known other than when Havana syndrome started. But others disagree. They say the evidence for microwaves is much stronger now, if not yet conclusive. The BBC has learnt that new evidence is arriving as data is collected and analysed more systematically for the first time. Some of the cases this year showed specific markers in the blood, indicating brain injury. These markers fall away after a few days and previously too much time had elapsed to spot them. But now that people are being tested much more quickly after reporting symptoms, they have been seen for the first time.

The debate remains divisive and it is possible the answer is complex. There may be a core of real cases, while others have been folded into the syndrome. Officials raise the possibility that the technology and the intent might have changed over time, perhaps shifting to try and unsettle the US. Some even worry one state may have piggy-backed on another’s activities. “We like a simple label diagnosis,” argues Professor Relman. “But sometimes it is tough to achieve. And when we can’t, we have to be very careful not to simply throw up our hands and walk away.”

The mystery of Havana syndrome could be its real power. The ambiguity and fear it spreads act as a multiplier, making more and more people wonder if they are suffering, and making it harder for spies and diplomats to operate overseas. Even if it began as a tightly defined incident, Havana syndrome may have developed a life of its own.

Illustrations by Gerry Fletcher